This week we are showcasing the work of Patricia Perez, a student in the School for Marine Science and Technology (SMAST) Master of Science Program in the Department of Fisheries Oceanography. Perez grew up in Maryland and obtained a BS in Marine Science from the University of South Carolina.

Perez then moved to New England to work as a fisheries observer, a position she held for three years. She worked briefly as an oyster farmer during this time and also spent a season as a sternman on a lobster boat out of Marshfield, Massachusetts. “Fisheries Observers deploy on commercial fishing vessels to collect data on the catch, bycatch, weather conditions, and fishing gear attributes” Perez explains. “This job allowed me to deploy from ports from Maine to Long Island and solidified my research and career interests I pursue today.”

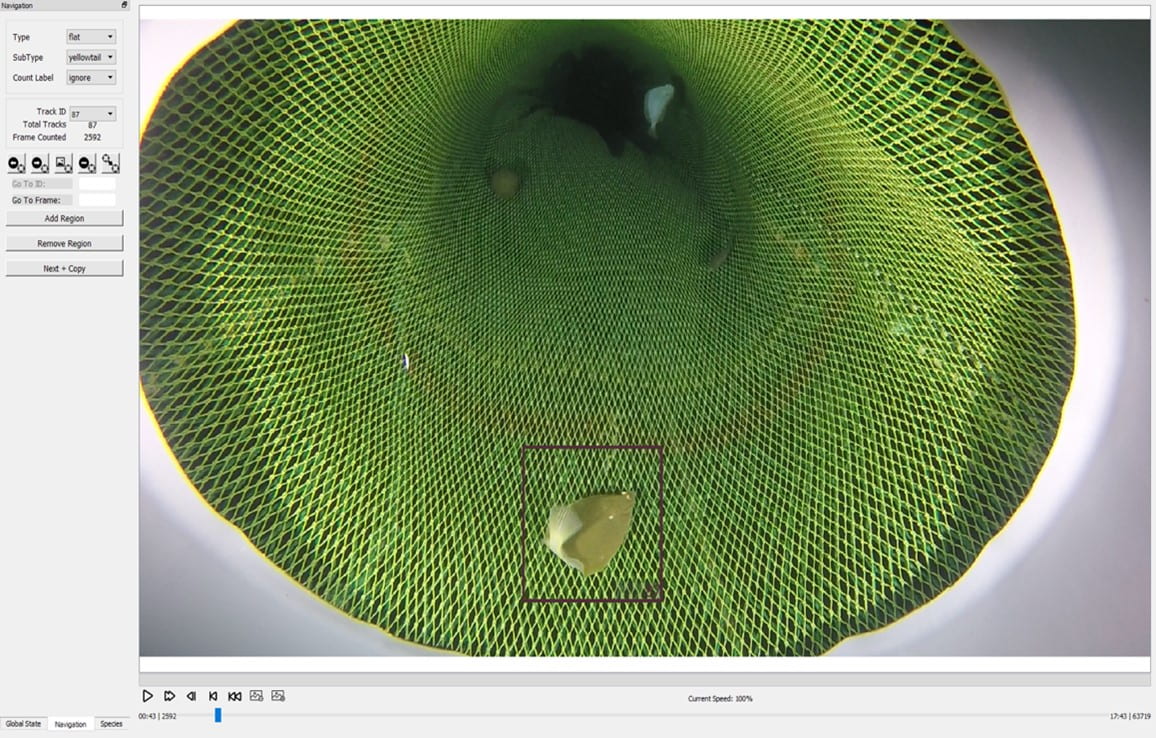

Perez’s Graduate thesis is centered around understanding what ecological influences are affecting a vulnerable stock of fish that may help explain why that stock is not recovering. “I am studying yellowtail flounder on Georges Bank,” Perez explains. “Georges Bank is a raised bank on our continental shelf between New England and Nova Scotia that serves as a historical fishing ground. yellowtail flounder were once plentiful on Georges Bank and Closed Areas (a type of marine protected area) were established to protect this species among others. But yellowtail flounder abundance has continued to decline since the early 2000s despite reduced catch limits. Therefore, I am exploring environmental and biological factors that may point to why this fishery has not recovered. To help answer this question, I am using data from a survey my lab at SMAST conducts – our “video trawl” survey. Our survey takes place in Closed Area II on Georges Bank aboard a commercial fishing boat where we drag a net along the seafloor to collect a sample of fish. Inside our net, lights and several video cameras are mounted to a plastic tube that holds the net open and records the fish as they pass through the net. The video is transmitted to the wheelhouse for us to watch in real time and also stored on a hard drive. Some of our tows (drags along the seafloor) are “closed” – meaning we bring the fish onboard to count, measure and take samples from. Other tows are “open” – meaning we leave the end of the net open, so fish may return back to the ocean, unharmed, after they pass through the view of the GoPro. Back on land in the lab, we watch the video stored on the hard drive to count and measure the yellowtail flounder.”

The photo above shows a yellowtail flounder captured by SMAST video footage as it swims through the net.

For Perez, building the relationship between fishermen and scientists is a crucial part of the work she does. “The most important aspect of my work is that our survey is conducted with fishermen on commercial fishing vessels,” she says. “After spending years aboard fishing vessels as a fisheries observer, it was important to me that my graduate research was collaborative with the fishing industry. Collaborative research is productive and integral for answering our research questions and works to develop trust between science and the industry.”

Like so many of us, the COVID-19 pandemic created significant setbacks for Perez and her research. “In April 2020, we were set to conduct another survey to continue our data time series, but were unable to complete the survey,” she says. “This not only created a gap in my data set, but also caused me to reconsider the research questions my advisor and I had originally intended to answer. But I think being flexible is an important skill to have when conducting field research.”

Tricia in the lab with a yellowtail flounder

Perez is especially proud of the innovative fishery survey technology her lab at SMAST has created. “Traditional fisheries surveys make short tows, count those fish on deck, and extrapolate those numbers to estimate how many fish are in that area of the ocean. Through our “video trawl” survey, we are able to count many more fish and avoid killing the fish. Any reduction in mortality is important for already depleted populations. The video can run and record for hours, allowing for larger sample size and covering a greater area than the standard bottom trawl survey. Both of these advantages translate to a better interpretation of the fish population size. Additionally, SMAST is working with CVisionAI to develop an algorithm for computer software to automatically count the fish as they pass through in the video, increasing efficiency and data processing times.”

This summer Perez and her lab will develop a technical paper and present their findings to the yellowtail flounder stock assessment scientists. “As part of the fisheries management process, stock assessment committees meet annually to consider new information, conduct stock assessments, and produce recommendations for fishery management councils,” Perez says. “I am excited to gain practical experience presenting my work and hope it may help to provide stronger scientific advice given to managers.”

After graduation Perez plans to find a position that would allow her to serve as a liaison between fishermen, scientists, and management. “There are a lot of competing objectives in the field of fisheries – it is essential to consider the sustainability of ocean resources and the coastal communities who depend on them,” she says.

Outside of her work with fisheries Perez can be found playing guitar, cooking seafood, and spectating the local surf community. She expects to graduate with her master’s degree this summer.

You can follow Tricia on Twitter at: @trishNfish